While Citrus College may appear to be a hallmark of diversity, the data actually shows a startling pattern of ethnic segregation.

The most recent California Community College Scorecard data on Citrus College’s student population shows that Approximately 61 percent of students are Latino, 17 percent non-Hispanic White, 9 percent Asian, and 4 percent are African-American out a total of 20,000 students.

It is clear that the student body is overwhelmingly Latino, with sizable White and Asian populations and much smaller African-American, Native American, and Filipino communities.

The campus’ student body population closely aligns with the predominant demographics of neighboring communities, which show stark signs of economic and ethnic segregation.

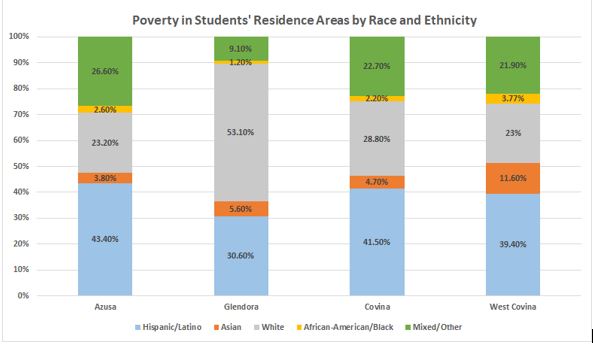

Data gathered in the 2017 Citrus College Fact book shows that most students come from the following cities: Azusa, Glendora, Covina, and West Covina.

The ethnic and racial compositions of students’ communities of residence show that Glendora is predominantly White while Azusa, Covina and West Covina are predominantly Hispanic or Latino as illustrated by the bar graph below.

chart by Sayedah Mosavi

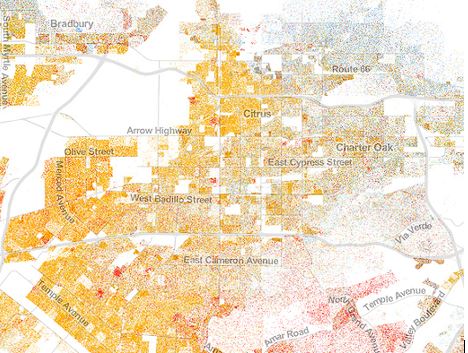

Data from the University of Virginia’s 2010 Census Racial Dot Map shows a clearer image of the racial and ethnic composition of students’ residence communities, highlighting existing patterns of segregation within surrounding neighborhoods.

The various colors on the map represent individuals within a racial group. Orange represents people who are Hispanic or Latino; red represents people who are Asian; blue represents people who are white and Green represents people who are African-American.

The most recent data from the Census Bureau’s 2016 American Community Survey shows that of the total percentage of people living in poverty, Azusa, Covina and West Covina show a much higher percentage of Latino and Hispanic people living in poverty, although the communities themselves are considered middle-income.

Glendora, a high-income community, has a higher percentage of white people living in poverty as shown in the graph below.

These patterns indicate the persistence of racial and ethnic segregation, which is correlated with economic disparities.

Leading members of the campus community are well aware of these patterns and have offered explanations for why this is the case in nearby communities.

“Historically, immigrant populations tend to live in familiar communities. You want things that are familiar because re-settling is hard work,” Marianne Smith, director of the Student Equity Grant, said. “We tend to move to places that feel a little comfortable to us.”

There are additional reasons as to why local communities appear ethnically segregated.

“I think also you have to look at the history of redlining and the kind of housing and access to mortgages and how communities were structured and built over time,” Smith said.

When asked if racial and economic segregation still affect local communities, David Kary, professor of Astronomy and chair of the Program Review Committee at Citrus College said, “There’s the more informal social and economic segregation that has happened that…That’s still a factor, and you can’t pull that out completely. It impacts where you live, your parents and what resources they have.”

Kary explained that, in the area around Citrus College, this mostly affects the Hispanic and Latino population.

Niki Shaw, professor of kinesiology and vice president of Academic Senate, had a strong response when asked the same question. “We never desegregated,” Shaw said. “We got rid of segregation in name only, but we never truly desegregated.”

Shaw continued to assert that the effects of segregation are still visible in economic inequity and education outcomes among historically underrepresented people.

At Citrus College, education achievement equity gaps are most seen with Hispanic and Latino students since they are a large part of the student body.

Smith explained that students come to college having already been exposed to education inequality in their k-12 schools, which partly depend on Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) funding from their surrounding communities.

“I’ve never been to an elementary school where the PTA never asks for money,” Smith said. “What do you think happens to equalized funding?” Smith asked, rhetorically. “Our k-12 schools, in general, are very unequal.”

Smith said that the effects of segregation plague the entire nation and that there is no perfect, immediate solution.

Kary also agreed with this sentiment. “There is no such thing as a cure-all,” he said. “It will take generations before we could possibly get passed that.”

However, both Smith and Kary were still hopeful for the future.

“I think the momentum right now is pulling us all into looking for solutions for equity gaps and working toward educational equity,” Smith said.

“The most important thing that, as an institution, that we can do is really improve the opportunities for students around us,” Kary said.

Smith discussed some of the programs that are already in place, which aim to reduce achievement gaps.

These programs include the Summer Bridge Program, the Promise Program, the Guided Pathways Project in addition to annual meeting with local k-12 school districts.

Smith explained that the Summer Bridge Program is aimed at helping recent high-school graduates transition into college, and the Promise Program is meant to reduce attendance costs for the first two years of college.

Arvid Spor, vice president of academic affairs said that the Guided Pathways Project also seeks to help reduce equity gaps by providing clearer paths for what courses students need to take to meet their educational goals.

Smith said that the meetings with local k-12 schools address education inequality by aligning k-12 curriculum with college-level courses in high school.

However, Shaw said that programs like Guided Pathways only address access issues. They do not do enough to engage the community.

“I don’t know that we’ve found our voice for who we are” Shaw said about the campus culture.

She explained that the college could represent “the variety of people that are welcome here” by publicly showing the core values of the campus community, which she hoped would encourage more student and community involvement.